Provides Access To An Array Of Culturally Appropriate Community-Based Behavioral Health Services to Improve Re-Entry Outcomes for Black Men

The common conception of aiding individuals affected by incarceration is to address practical needs such as housing, food, and employment. Yet, these services are often insufficient when the core of their issues is related to psychological factors.

African American males’ consequences of low social status due to incarceration are compounded by systemic racism and stereotypes. Consequently, the portrait of African American males puts them under heightened scrutiny and increases the number of unfavorable encounters with police and society.

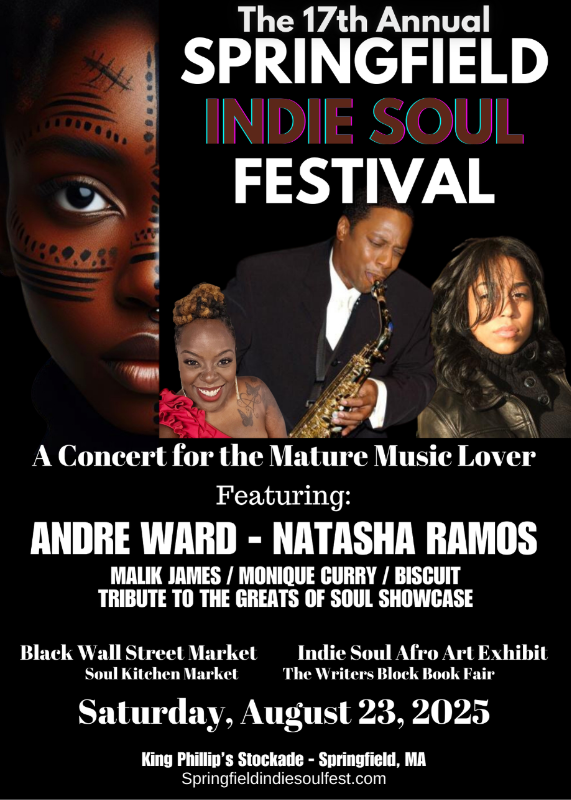

To address the issue in Springfield, MA, Founders Della Blake, and Donald Perry came together to explore strategies to support the community, specifically African American men, around successful re-entry into the community. There are plans to duplicate services for women in the future.

Blake and Perry created an organization called the Black Behavioral Health Network (BBHN). BBHN provides access to an array of culturally appropriate community-based behavioral health services. Our focus is on positive treatment outcomes for all individuals within our care, African Americans, BIPOC and others within the Greater Springfield area. Our goal is to address service gaps and public health disparities experienced by individuals, families, military veterans, those affected by addiction, criminal justice issues, homelessness, unemployment/underemployment, and other social injustices that affect the quality of life for those populations.

Blake said that our incarceration numbers in this country are incredibly high compared to other demographics. So, we want to affect recidivism and relapse, and we’re looking at the research about why people of color don’t complete treatment, which is one of the reasons the Black Addiction Counseling Education program exists. Blake said that many Black men get violated and return to the criminal justice system due to minimal offenses. Blake noted that it was essential to expand their Board of Directors that also include people from the impacted populations to help shape the outcomes of their work. Founding members include Ernest Allen, Richard Johnson, Clinton Harris. Board members include: Lisa Allen,

Dallas Clark, Garnett Martin, Nicole Darden and Joaquin Suttles.

Blake said that because BACE is a workforce development program, they are also creating opportunities tomore certified and licensed Black people into the fields of substance use and Addiction counseling.

We hope it will affect black people completing treatments because they can identify with the service provider. A Pennsylvania study in 2013, indicated that the majority white service providers in the field is a factor as to why black clients do not complete treatment.

The Latino Addiction Counselor Education (LACE) and The Black Addiction Counselor Education (BACE) Programs are unique in Massachusetts because they are the only ones of their kind across the country. However, in Boston, where the funding comes from many programs and services, there and elsewhere are still grounded in systemic racism.

Blake said I talked to many people who enroll in the BACE program. They talk about their struggles within substance use agencies dealing with colleagues and racist experiences they have working in these treatment environments, which are supposed to be contrary to that kind of climate required for people to get well. It’s not a conducive climate if racism exists to support people working toward recovery, you know, because it’s not empathetic. Discrimination and racism comes with negative energy and attitudes and is not conducive to people receiving the help they need.

Barriers to Success

Finding permanent employment is perhaps the most common obstacle for many re-entry populations to experience, because it is essential to get because finding a job is a way of securing income and stability.

Blake says we need to examine existing historical services and supports because the data proves they can’t come out of jail and treatment centers and be given a list of jobs and told to go out and find employers. So, we need to pay more attention to the details and help our population get deliberately connected with the community’s support systems that will help them stabilize their lives. So, we need to help them gain employment.

Our job is to help them set up safe and sober housing because the incidence of homelessness amongst African Americans is exceptionally high, so we need to help them with housing. We need to help them with black mental health services, more specifically, services with clinicians who can identify with the history of trauma that still affects us as a people in terms of racism and discrimination.

Blake noted internal biases within the community; she said that people still have their thoughts, opinions, and attitudes about ex-prisoners and substance users. However, she said she noticed many churches and pastors are interested in opening sober homes to support these populations coming back into the community. Blake says she is not sure, however, if they understand how to do that or how to connect with the people.

Blake said our communities have normalized trauma. Tragically, we have learned to live with the trauma for many years if not a lifetime; we find ways to deal with trauma. It is starting to come into perspective that there’s no shame or stigma behind needing counseling or mental health support services. But, Blake continued, we’re just beginning to embrace that as a community.

Blake said before this awakening, we did not have the information, resources, or skill sets, but that is changing. There are more of us going to college, getting into the field, and becoming psychologists and clinicians. More Black people are starting to embrace and challenge those stigmas and we are here to do our part.