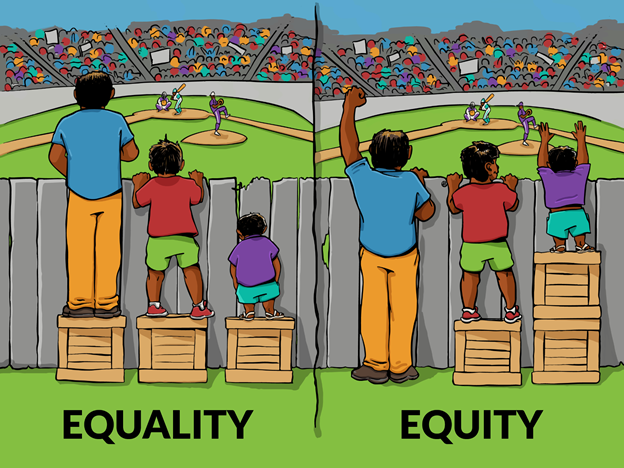

By now, most of us have seen the above cartoon image of three people standing at a fence to view a baseball game. It’s an image of America’s greatest crate challenge; distinguishing the difference between equality and equity.

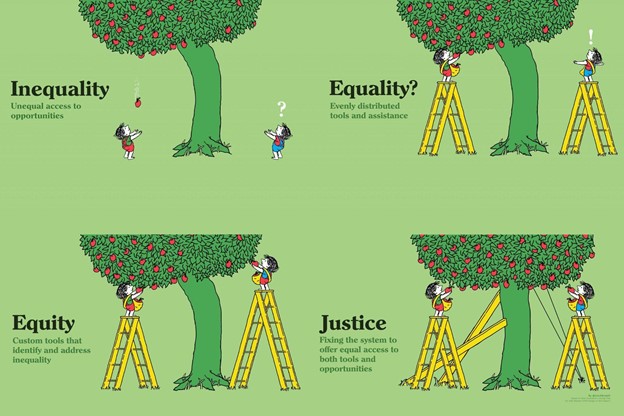

This cartoon has come under some scrutiny since created in 2016, some believing it was an example of White Supremacy in disguise. However, for a better visual representation of Equity vs. Equality, Tony Ruth’s example using the Giving Tree (below) shows how to provide fair opportunities and the effort needed to address the injustice that caused the inequities.

As a community organizer, equity is a means to address the longstanding effects of disenfranchisement and cultural erasure by various forms of systemic oppression. Equity means creating and preserving a fair and just society, community, or organization in which those folks who’ve been historically and systemically excluded are now systematically and intentionally included.

Strategies built to heal inequities should be steeped in historical context. Thus, for example, housing equity initiatives must work to undo the effects of redlining and predatory loan programs; health equity initiatives must consider the untrustworthiness of American medicine and the profits driving treatments rather than cures.

Having the history of disenfranchisement in focus is also imperative for cultivating equity in America’s education system. Educators, administrators, staff, students and parents, must remember the history of hindrance Black and Brown students faced throughout the provenance of American education.

Black people were the only people legally barred from learning in America. Despite this, enslaved Africans developed their version of public scholarship. Clandestine Black schools were made out of the dark corners of cabins or hiding in plain sight, singing in the fields and yards of plantations. As a result, ancestral African knowledge and customs melded with early colonist ideas and language, forming new understandings and speech.

At the end of slavery in America, folks like Robert Moton, who Booker T. Washington inspired, built thousands of schools across America. Some schools, funded by Julius Rosenwald and a handful of wealthy donors, were multi-room buildings walled with bricks community members formed themselves, like Tuskegee and Colman College. Others were one-room shacks made of spare wood and metal collected by community members, like my grandmother’s grade school on Union Street in Westminster, Maryland.

By the time of the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954, these schools had countless students and sharpened the skills of an innumerable amount of teachers. Desegregation, believed to be a way to deter the racial divide, only widened disparities. Black, Brown, and Indigenous students were and still are, forced to carve up their culture, deemed savage or unacceptable, to replace it with Eurocentric standards structured by western colonization. Black teachers and administrators were fired or sent to White schools where they were outnumbered, underpaid and overqualified. An estimated 38,000 teachers lost their jobs in the southern states alone.

The history of Black schools in the United States reveals that faculty, staff, and students shared an understanding of their need for survival and worked towards their liberation in a collective effort. The question then becomes: How can Black students or educators feel affirmed or successful in an institution that isn’t fully supportive of their leadership, freedom, and intellectual growth but deems them lesser?

Equity work in education means accepting the most complex parts of American history and reconciling the effects of disenfranchisement in education. This isn’t “cancel culture” but context culture, transforming our perspectives to understand the work and truths that lay before us entirely.

White privilege is being able to take the offerings of education for granted. Seemingly, America’s education system has been ready-made and waiting for White folks. Schools are where cultural Whiteness is not just welcomed but centered and expanded, while BIPoC students are overpoliced into compliance. Economically, schools that serve a predominantly White student body are less likely to find themselves in need, in contrast to poor Black schools called, sometimes called “fail factories.”

Often equity comes off like this confusing, ambiguous catch-all term used to describe diversity and inclusion efforts; work intended to correct these injustices. Some of my associates offer an immediate eye roll to organizations that claim to be doing equity work. To them, corporate efforts to address inequities prove to be shallow; hiring another Black or Brown employee or hosting a day-long diversity training won’t upend the culture that maintains inequities. Even further, these efforts do not rebuild the relationships within the greater community most harmed by marginalization.

Though I agree with many of my friends who feel this way, I understand equity to be the first step of many. Interrogating our histories acknowledges how sterilized our stories have become and provides insight as to what parts of our society need repair. This work goes beyond thoughts and prayers, beyond hiring someone of different skin color. Equity is much more than ensuring everyone has an equal opportunity. Equity initiatives must focus on transforming policy and practice in a way that bolsters fairness and holds accountable those who may continue to disenfranchise community members. Equity is simply the beginning of a long journey towards justice.